Crazy Horse Against the Machine

The life and death and rise of a Thunder Dreamer.

We were sitting at a coffee bar in Apache Junction, Arizona, when I noticed the silver medallion propped against the espresso machine. It bore the bust of a shirtless man astride a fuming steed. His long, loose hair flowed behind him as he pointed forward with one muscular arm. I leaned against the bar, squinting:

Is that… Crazy Horse?

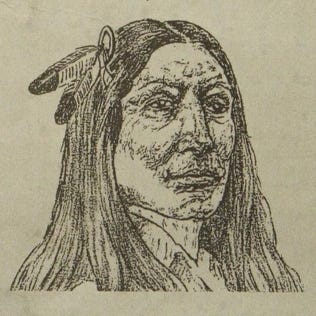

The famous Oglala Lakota war chief never agreed to have his picture taken, it is said. Apart from a few general traits—sharp nose, light brown hair, smaller build—no one living knows quite what he looked like. I recognized the medallion as a replica of the Crazy Horse Memorial in the Black Hills, or how the monument is projected to appear once completed. Zach and I had driven past the site just four months earlier on a camping trip. One day, perhaps 100 years from now, Crazy Horse will be the largest mountain carving on Earth.

The barista preparing our drinks looked like a barista: canvas apron, tattooed forearms, curly red mohawk tucked beneath a backwards cap, and the waxed mustache. He appeared to be wearing a pair of Meta’s AI glasses. When he learned we were visiting from South Dakota, he shared that his parents used to own a house in Custer. He praised the beauty of the Black Hills and the Crazy Horse Memorial gift shop. Unfortunately, the house was haunted by “paranormal shit.”

He explained that, while staying with his parents years ago, he “got choked” one night. We asked what he meant by this. He said he was lying in bed when suddenly something fierce began wringing his throat:

“The only thing I knew to do in that scenario was just say Jesus! Jesus! Jesus! So that’s what I did, and it let go.”

He then saw a dark figure slip into the closet. Leaping from bed, he switched on the lights—the bulbs flashed, then exploded, and the demon was gone.

“You know,” he said, “the whites stole the Black Hills from the natives. That land is cursed.”

His parents sold the house and moved back to California.

The Lakotas were not the first Native Americans in the Black Hills, but they had more or less secured the region from rival tribes by the year 1800. The Hills offered abundant game, vegetation, timber, and shelter from the surrounding plains. Who wouldn’t want to claim that majestic mountain fastness known as Paha Sapa?

As American expansion moved west into the 19th century, conflicts arose between the Lakotas, Oregon Trail pioneers, and—with frustrating regularity—the U.S. military. This eventuated in a series of treaties between the Lakota people and the U.S. government, which acknowledged, among other things, the tribe’s sovereignty and claims to specific land. Remarkably, the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie included all of present-day South Dakota west of the Missouri River within the Great Sioux Reservation, of which the Lakota were assured “absolute and undisturbed use and occupation.” By 1874, however, the Fed had found a compelling reason to rethink its promises.

Gold.

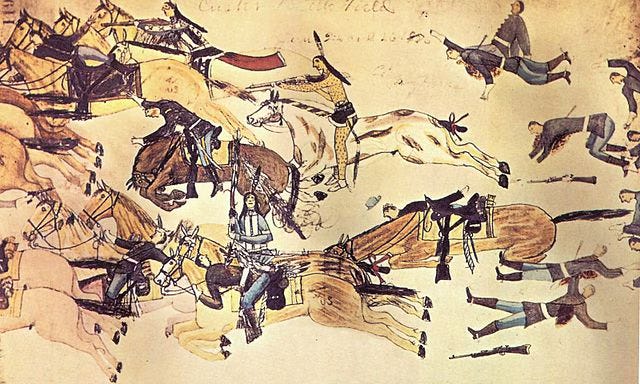

The Black Hills Gold Rush precipitated a string of historic calamities: wild encroachment and gold mining on Lakota lands, followed by the near-extinction of its bison; Custer’s demise at the Battle of the Little Bighorn; and, ultimately, the confiscation of the Black Hills by the U.S. government in violation of its 1868 treaty.1 At the center of this tectonic collision was a peculiar man named Tasunke Witco, Crazy Horse.

Though shrouded in legend, the basic shape of his life is clear enough:

Crazy Horse was born around 1840 near Bear Butte, just outside the Black Hills. He lived his thirty-seven or so years on the great grassland steppe of North America. Like all Lakota boys of his time, he was raised to shoot a bow, forage, hunt bison, ride horses, steal horses, raid, fight, scalp, practice virtue, observe sacred rituals, honor his elders, and fear Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit in all things. As a young man he received a formative vision which seemed to predict both that he would become a great warrior and that his people would one day betray him. Pensive and taciturn by nature, he nonetheless led the Lakota in several pivotal victories against the oncoming “Long Knives” of the U.S. Army. Crazy Horse never signed a treaty, never accepted government handouts or confinement to a reservation. In the end, he was indeed betrayed by his friends, and suffered a fatal bayonet wound to the gut by a no-name Army soldier at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. Refusing the cot they offered him, he bled out his final moments in the dust.2

Whatever else might be said of him, Crazy Horse was a man who lived on his own terms. Yet even this is an oversimplification. Certainly, he was something of a maverick, even a loner, but he also possessed unyielding loyalty to the Lakota tribe and way of life. As Larry McMurtry put it, “Crazy Horse was loved and valued by his people as much for his charity as for his courage.”3 This is one of the more forthcoming statements in McMurtry’s terse biography, which charges other writers with mythifying Crazy Horse the man. He cites with approval the gripes of historian George E. Hyde:

They [fanatic historians] depict Crazy Horse as a kind of being never seen on earth: a genius at war yet a lover of peace; a statesman who apparently never thought of the interest of any human being outside his own camp; a dreamer, a mystic, and a kind of Sioux Christ, who was betrayed in the end by his own disciples… One is inclined to ask, what is it all about?

Everything I’ve read on Crazy Horse grants the point eventually: this “Sioux Christ” was and remains an enigma, such are the limits of history. After all, when he spoke, he spoke Lakota. He preferred solitude and spent all but the final months of his truncated life avoiding white civilization with its journalists and photographers. On the other hand, Crazy Horse’s protean mystique arises not only from the historical lacunae, but equally from the few firm facts we do have about him. Above all, the paradoxes of his life begin to cohere, so to speak, when we remember that Crazy Horse was a Thunder Dreamer.

Crazy in a Sacred Way

Many Lakota youth underwent vision quests to seek spiritual guidance for their lives. Of those who obtained visions, but few made contact with the Thunder Beings of the West, or Wakíŋyaŋ. In Lakota cosmology, the Thunder Beings were spiritual deities associated with storms, the sky, and the west.4 They were believed to bestow special powers on the chosen Thunder Dreamer, provided he fulfilled the substance of his vision. By most accounts, Crazy Horse was such a dreamer.

The vision that would determine the course of his life has been variously told and interpreted (not unlike the famous dream of his younger cousin, Black Elk, also a Thunder Dreamer). After fasting alone on the plains for several days, Crazy Horse was visited by the Wakíŋyaŋ in the form of a spirit-horseman emerging from a lake. The rider is typically described with lightning bolts and blue hailstones painted on his body, a reddish pebble somehow tucked behind one ear, and a single feather adorning his unbraided hair. A red-tailed hawk soared above. The rider passed unharmed through a flurry of arrows and bullets, but then a band of his own people rose up, seizing him, and pulled him down from behind. Thus the dream ends.5

To me, the details of the vision are less significant than the lifelong purpose Crazy Horse—through the guidance of his elders—found in it. The rider was him, of course, or somehow foreshadowed the man he was to become. Lakota historian Joseph M. Marshall III explains:

Anyone who dreamed of the Thunder Beings, the Wakinyan, was called upon to walk the path of the Heyoka (heh-yo’-kah), also known as wakan witkotkoka, which is roughly translated as “crazy in a sacred way.” A Heyoka was a walking contradiction, acting silly or even crazy sometimes, but generally expected to live and act contrary to accepted rules of behavior. In doing so a Thunder Dreamer sacrificed reputation and ego for the sake of the people.6

Drawing on Lakota oral traditions, Marshall suggests that Crazy Horse embraced the vision as a summons to humility and sacrifice over vainglory. It was customary for Sioux fighters to boast of their exploits on the battlefield, the enemy scalps they’d cut. Crazy Horse would remain a warrior—would become the greatest Lakota warrior of his day—but now he was to forsake all such vanity. He must dress simply, forgo the spoils of war (including scalps) and, most importantly, provide for the elderly and vulnerable in his camp. So long as he adhered to his vision, Crazy Horse would remain untouchable in war.7

One is tempted to speculate about all this. Was the vision merely a self-fulfilling prophecy that manifested the sort of hero young Crazy Horse already aspired to become? Did it endow him with supernatural powers, or simple human courage?

We will never know. What we do know is Crazy Horse seemed to take the call of the Heyoka seriously. Even as he led his people in resistance to the will of “Great Father” back east, he grew strange in their eyes. One evening he would return from a hunt or raid to distribute provisions among the needy and encourage the young; the next he would pace the camp without acknowledging a soul, as if lost in thought. All his life he craved solitude, and the mounting pressures of leadership and brute survival would drive him onto the vast isolation of the plains, where he could reflect and pray to Wakan Tanka for guidance.8

In the savage winter of 1876, Crazy Horse’s family began voicing concerns over his tendency to disappear into the hills for days on end. Black Elk Speaks gives this account:

He hardly ever stayed in the camp. People would find him out alone in the cold, and they would ask him to come home with them. He would not come, but sometimes he would tell the people what to do. People wondered if he ate anything at all. Once my father found him out alone like that, and he said to my father: “Uncle, you have noticed the way I act. But do not worry; there are caves and holes for me to live in, and out here the spirits may help me. I am making plans for the good of my people.” He was always a queer man, but that winter he was queerer than ever.9

Like biblical prophets and other holy fools of old, the Heyoka served as a kind of contrarian social critic—subverting the status quo through his odd behavior, declaring difficult truths from the wilderness.10 McMurtry posits that, had it not been for his duty to his languishing followers, Crazy Horse might have remained a cave-dweller for good.11 Instead, starving and surrounded by a seemingly unstoppable foe, he made the inevitable decision to turn in.

Sort of. In his final negotiations with the Army, Crazy Horse was led to believe he might get his own agency out of the deal, a modest plot of land in the Powder River country of Wyoming. The actual plan was to ship him to an island prison off the Florida Keys called the Dry Tortugas—a wildly unimaginable scenario. Well, misunderstanding and deception led to confusion and fear, and Crazy Horse was dead before they could leave Fort Robinson. He never saw the ocean.

Gold in the Grass

While writing this essay I have been reading Paul Kingsnorth’s new book Against the Machine. Kingsnorth argues that Western civilization, since at least the Enlightenment, has been dominated by “The Machine,” which he defines as “an intersection of money power, state power and increasingly coercive and manipulative technologies, which constitute an ongoing war against roots and against limits.”12 The Machine seeks total control of the world and will subjugate or bulldoze whatever stands in its way: nature, religion, culture, humanity itself. Ironically, in building this Machine, says Kingsnorth, the West has effectively colonized itself, selling its soul to the unholy trinity of big tech, big money, and limitless industry.

Staying human in the age of the Machine will therefore require a return to roots and limits. Specifically, we must embrace the “Four Ps”:

Past. Where a culture comes from, its history and ancestry.

People. Who a culture is. A sense of being ‘a people’.

Place. Where a culture is. Nature in its local and particular manifestation.

Prayer. Where a culture is going. Its religious tradition, which relates to God or the gods.13

One way to view the life of Crazy Horse is as the story of a man, at once exceptional and ordinary, who found himself snagged in the gears of the Machine. Kingsnorth’s term is capacious enough to encompass the various factors typically invoked to explain the Plains Indian Wars—colonization, Manifest Destiny, railroads, etc.—while highlighting how the whole fiasco was, crucially, driven by specific economic interests. That is, avarice.

Except in passing, Euro-Americans largely ignored the Black Hills until they heard the rumors of gold. On his 1874 expedition through the region, Custer hyperbolically reported discovering the precious metal “from the grass roots down.” Days later the Bismarck Tribune predicted the Black Hills would become the next “El Dorado of America.” Thousands of miners flooded the Hills. When the U.S. government realized it could (would?) no longer prevent them, it simply seized the land from the Lakotas.

That land represented the “Four Ps” of Crazy Horse—though “represent” is far too abstract a word. The Black Hills region quite literally comprised his past, his people, his place, even his prayers. The treaties meant nothing to him. Nor did he suppose the Lakota people “owned” the Black Hills as Whites understood private property. Paha Sapa was his home, the earth he knew and loved. This is why he gave his life defending it; this is why the Machine killed Crazy Horse.

It is easy to sympathize with those “Agency Indians” who surrendered in the face of impossible odds. Abject track record aside, the Machine promised clothing, food, and shelter. And booze. Better to accept an attenuated existence on some reservation than death by starvation, bayonet, or bullet wound. Right? And yet there is a reason the Lakota chose Crazy Horse for their mountain. The Machine may have killed him, but it never tamed him.

“The Heyoka is a man taller than his shadow,” writes Wambli Sina Win. These days, Crazy Horse casts a colossal shadow.

I had already been thinking about him.

On my flight to Arizona, I happened to read chapter 6 of Ian Frazier’s modern classic Great Plains, the chapter on Crazy Horse. Frazier believed the death of Crazy Horse “shrank” America in our collective imagination. In its war against roots and limits, the Machine—call it colonization, empire, capitalism, whatever—the Machine smothered the vision of liberty and justice that inspired America’s founders. “Like the center of a dying fire,” Frazier writes, “the Great Plains held that original vision longest. Just as people finally came to the Great Plains and changed them, so they came to where Crazy Horse lived and killed him.”14

Even so, the great, granite Thunder Dreamer rises over his Black Hills, a paradoxical symbol of freedom and fidelity, strength and submission, solitude and solidarity. Reflecting on it all moved Frazier to conclude his chapter with a startling passage that verges on hagiography. I quote at length:

Personally, I love Crazy Horse because even the most basic outline of his life shows how great he was; because he remained himself from the moment of his birth to the moment he died; because he knew exactly where he wanted to live, and never left; because he may have surrendered, but he was never defeated in battle; because, although he was killed, even the Army admitted he was never captured; because he was so free that he didn’t know what a jail looked like; because at the most desperate moment of his life he only cut Little Big Man on the hand; because, unlike many people all over the world, when he met white men he was not diminished by the encounter; because his dislike of the oncoming civilization was prophetic; because the idea of becoming a farmer apparently never crossed his mind; because he didn’t end up in the Dry Tortugas; because he never met the President; because he never rode on a train, slept in a boardinghouse, ate at a table; because he never wore a medal or a top hat or any other thing that white men gave him; because he made sure that his wife was safe before going to where he expected to die; because although Indian agents, among themselves, sometimes referred to Red Cloud as “Red” and Spotted Tail as “Spot,” they never used a diminutive for him; because, deprived of freedom, power, occupation, culture, trapped in a situation where bravery was invisible, he was still brave; because he fought in self-defense, and took no one with him when he died; because, like the rings of Saturn, the carbon atom, and the underwater reef, he belonged to a category of phenomena which our technology had not then advanced far enough to photograph; because no photograph or painting or even sketch of him exists.15

Since Frazier wrote this in 1989, a reputable sketch has in fact emerged, drawn by a Mormon missionary who consulted Crazy Horse’s sister for accuracy:

As for the monument, some doubt it will ever see completion, so adamant is the mountain, so slow the chisels of men. A recent article in South Dakota Magazine takes a more optimistic view, reporting that new technologies—including a 270-foot remote-controlled crane and a German-made robotic arm—have accelerated construction considerably. Crew leaders are even toying with completion dates within their lifetimes. The only catch? “Robotics and some other advanced technologies don’t function well when temperatures fall below 40 degrees.”

We will never capture him, this strange man of the Oglalas. He is out alone in the cold, among the caves and holes, making plans for the good of his people.

Personal Postscript

After a solid year of grappling with Crazy Horse and the history of the Black Hills, I have felt obliged to write this piece, though I thought twice about publishing it. I don’t expect (m)any of you to share these preoccupations of mine. The temptation is to reduce Crazy Horse to a handful of relevant “life lessons,” a temptation I have not entirely resisted. True, Crazy Horse was a mere man. We would doubtless be appalled by the violence he was capable of. He neither gave his life for the sins of his people nor rose again on the third day. And yet I can’t help but admire his fortitude. I only hope I would have acted as he acted, had I faced what he faced.

Insofar as what he faced was the Machine of which Kingsnorth writes, Crazy Horse remains a model for those of us attempting to maneuver the Machine’s latest machinations, just as he remains a perpetual symbol of strength to the Sioux people. He reminds us all that a life devoted to a particular past, place, people and prayer may be met with perplexity and scorn in this world, but that such a life can be good, even great, regardless.

This final move was also a violation of the Fifth Amendment, according to a 1980 ruling by the Supreme Court. See Jeffrey Ostler, The Lakotas and the Black Hills: The Struggle for Sacred Ground (New York: Penguin Books, 2011).

This is my synthesis of material, sometimes conflicting, found in the following sources: Bray, Kingsley M. Crazy Horse: A Lakota Life (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006); DeMallie, Raymond J., and Elaine A. Jahner, eds. Lakota Belief and Ritual (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1980); Frazier, Ian. Great Plains (New York: FS&G, 1989); Gardner, Mark Lee. The Earth Is All That Lasts: Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and the Last Stand of the Great Sioux Nation (New York: Mariner Books, 2022); Kadlecek, Edward & Mabell, eds. To Kill an Eagle: Indian Views on the Last Days of Crazy Horse (Boulder, CO: Johnson Books, 1993); Marshall, Joseph M., III. The Journey of Crazy Horse: A Lakota History (New York: Viking Penguin, 2004); McMurtry, Larry. Crazy Horse: A Life (New York: Penguin Books, 1999); Neihardt, John G. Black Elk Speaks (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2014).

McMurtry, Crazy Horse, 2.

Bray, Crazy Horse, 40–43.

Marshall III, The Journey of Crazy Horse, 71–73.

Marshall III, The Journey of Crazy Horse, xvi.

Kadlecek and Kadlecek, To Kill an Eagle, 12–13.

Bray, Crazy Horse, 263–264.

Neihardt, Black Elk Speaks, 84.

They were also notoriously funny, similar to the court fools of the Middle Ages. If Crazy Horse had a sense of humor, it doesn’t show much in the historical records. His younger cousin Black Elk, however, was known for his goofy playacting, including pretending to converse with horses and occasionally wearing his wife’s clothing to mass.

I once heard a Lakota man describe the communal character of Native cultures in this way: “Western people say, ‘I am a citizen; therefore I have rights.’ Lakota people say, ‘I am a citizen; therefore, I have responsibilities.’”

Paul Kingsnorth, Against the Machine: On the Unmaking of Humanity (New York: Thesis, 2025), 38.

Kingsnorth, Against the Machine, 131.

Frazier, Great Plains, 118.

Frazier, Great Plains, 117–18.

Fascinating stuff Cameron, thanks for sharing. I only knew the barest facts about Crazy Horse's life. And I never knew you were in SD! One of the few states I don't have any subscribers haha. I'll have to make a visit out there one day, it sounds and looks beautiful.

"The Machine may have killed him, but it never tamed him." Wow.

I remember seeing the Crazy Horse monument years ago on a roadtrip, when I was still a kid. Even at that young age, I remember feeling struck with awe and thinking what a shame it was (is!) that the construction was not being done in greater earnest.

Crazy Horse demonstrates a kind of unflagging conviction and rule of life that not even death or defeat can kill. Thank you for drawing our attention back to him!!